Shots Fired: Understanding Gun Violence in Mansfield

This is the fifth installment in a nine-part series focused on gun violence and possible ideas to address this issue in Mansfield. These stories will run on consecutive days starting Oct. 8 and running through Oct. 16. Links to the previous four parts of the series may be found at the end of this piece.

MANSFIELD — When Jim Kulig came to Mansfield in 1968, his first job was as a casework supervisor in the youth dormitory of the Ohio State Reformatory, which housed around 200 young men ages 16 to 19.

That’s where he met Sid.

At 19 years old, Sid had already been in prison for three years when Kulig met him. He described Sid as a quiet, introspective person who was also bright, even taking college classes and training himself to be a musician.

“He was a wonderful guitarist,” Kulig said. “If you listened to a Wes Montgomery record and you heard Sid play, you couldn’t tell the difference.”

Sid was released from the Reformatory two years later. Kulig felt he had adequately prepared the young man to reintegrate into society. He even got special permission to do home visits in Cleveland and meet Sid’s friends and family.

Yet two months after his release, Sid pulled a gun on a bartender at a neighborhood bar. He was shot and killed by an off-duty policeman. Kulig was 26 years old.

“For a young guy who was going to save the world, it rattled my belief system,” Kulig said. “It said something about educating me about the power that I didn’t have, and the demons that exist in people’s lives to support their making bad choices still.”

Jim Kulig: “Every person has strengths, and sometimes those strengths get hidden away with behavior that doesn’t seem appropriate. But choices are something that all of us have.”

Kulig kept in touch with Sid’s mother long after. They never quite figured out why Sid made the choices that led to his untimely death more than 50 years ago.

Since then, Kulig has served as executive director of Family Services of North Central Ohio, overseeing the merger in 1975 with the Richland County Mental Health Association. He served as CEO of what is now known as Catalyst Life Services and he worked as juvenile court administrator before his retirement 10 years ago.

He still believes change is possible for everyone. But thanks to Sid, he’s also learned it’s not always that simple.

“Every person has strengths, and sometimes those strengths get hidden away with behavior that doesn’t seem appropriate,” he said. “But choices are something that all of us have.”

Understanding why a young person may choose to turn towards violence is a question that plagues many more than just Kulig. Unfortunately, no single factor explains why some youth may perpetuate or even experience violence.

Culture Of Fear

Homicide was the third-leading cause of death for young people ages 10-24 in 2016, according to youth.gov — and the leading cause of death for African-American youth. Youth violence is typically defined by young people hurting their own peers.

These statistics have become reality in Mansfield recently, with nine homicides handled by the Mansfield Police Department in 2023, the most in at least the last decade. Eight of the nine victims were under the age of 40, and six were under the age of 30.

It’s causing an increase in anxiety for Mansfield’s youth, according to counselor Buffi Williams. She serves as program director for the “A Beautiful Mind” organization, which creates programming focusing on the emotional needs of youth.

This heightened state of anxiety and trauma causes a spike in cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. It causes youth to feel like they are constantly in “a war zone,” Williams said.

“A lot of kids feel our community is not a safe place,” she said. “They need to feel they can walk down the streets and not feel like something is going to happen to them. And what we call ‘the streets’ is their community — where they play and ride bikes and walk to their friends’ houses.”

In fact, one young person Williams spoke to said he carries a weapon. It’s not because he has anything against anyone, he said. It’s what he feels he must do to keep himself safe.

“They feel like a level of street credibility is somewhat necessary for safety,” Williams said.

Buffi Williams: “A lot of kids feel our community is not a safe place. They need to feel they can walk down the streets and not feel like something is going to happen to them. “

Brad Strong, a 30-year educator within the Mansfield City Schools district, said the amount of trauma young people are living with is at an all-time high.

“They’re living their lives in this trauma, and they don’t know how to respond properly,” Strong said. “They’re staying (at this heightened level) for so long they don’t know any different.”

It’s also why Strong has observed some students are living only to survive their day-to-day life, instead of actively planning for their future.

“I was talking to a young person and they used the word ‘legend,’ which means when you die young, you die a legend,” he said. “ This is the mindset of some of our kids.”

Backed By Research

Prevention, intervention and treatment strategies that are trauma-informed are key, according to youth.gov. This type of care is focused on understanding the causes and consequences of trauma to promote resilience and healing.

Some of those causes are defined as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood and can increase the likelihood of future violence victimization and perpetration.

ACEs and other social determinants of health, such as living in under-resourced or racially segregated neighborhoods, can cause extended or prolonged stress. This kind of toxic stress can affect a child’s attention, decision-making and learning.

“Some children may face further exposure to toxic stress from historical and ongoing traumas due to systemic racism or the impacts of poverty resulting from limited educational and economic opportunities,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

A 2021 study researching the relationship between childhood neglect and violence in adulthood found there is also evidence that housing, financial and food insecurities play a role in the cycle of violence.

“These basic needs insecurities place previously neglected individuals at increased risk for violence by raising stress levels, reducing feelings of control, and/or increasing feelings of anger, resentment, and alienation, which in turn, serve to trigger antisocial behavior and violent offending,” the study reads.

“It is also possible that these insecurities lead to uncertainty about one’s ability to survive in the world.”

It Takes A Village

Kulig said the ACEs study can help people understand why someone would pick up a gun.

“There’s been no evaluative tool that is an accurate predictor of violence,” he said. “But we now know better what it is that kids from infancy and beyond need that creates an opportunity for them not to commit a violent act.”

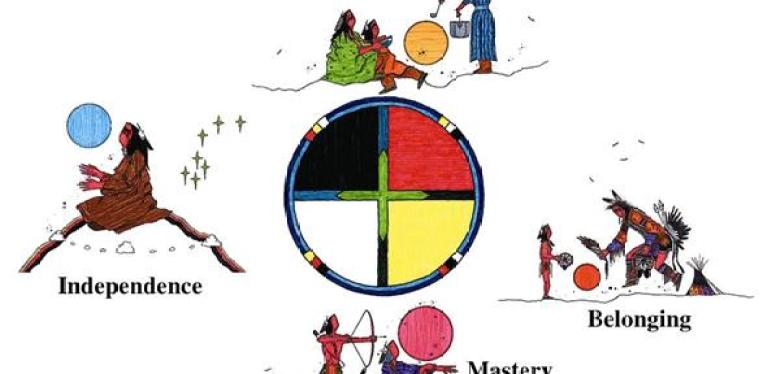

What kids need, Kulig said, is simple. Indigenous American culture illustrates these needs through the “Circle of Courage,” a model of youth empowerment that identifies four vital signs for positively guiding youth: belonging, mastery, independence and generosity.

In order to thrive, Kulig said, young people must have opportunities to experience each of the aspects in the circle.

“If any of those things are missing, there’s a void in that person’s life,” Kulig said. “If the circle is not broken, the kid will likely be okay.”

Williams said the most effective strategy is to teach youth about social skills, cognitive processing and communication abilities to lower the effect of negative social determinants of health.

“I’ve been in social services for about 30 years, and I believe the risk factors will always be there,” she said. “So my goal instead is, how does being in poverty hurt you? How does your dad being imprisoned affect you? And then we can put a shield around you so it doesn’t affect you as much.

“But the idea that we will live in a society with no risk factors and no barriers is a waste of time.”

Williams’ main goal for the next generation in Mansfield is to create a new narrative for the community.

Instead of a culture of fear and violence, she hopes to introduce values like hope, communication, compassion, understanding and forgiveness.

“If we begin to give those things again, that’s how it can grow into an ideal that we could be a community by having simple values,” she said.

She also believes it takes a village to raise a child — an ideal that Kulig also firmly holds.

“I believe very clearly that children don’t grow up in programs, children grow up in communities,” he said. “It is the responsibility of the community of Mansfield to support kids in growing up positively.

“Programs distract from community because if you’re relying on a program to fix things, you don’t have to face yourself with responsibility.”

A Different Life

Kulig said he learned long ago not to accept responsibility for anyone’s life but his own. Yet he still holds responsibility for a drawn portrait of an 18-month-old little boy belonging to a former Reformatory resident named Robert.

Robert asked Kulig to hold the portrait of his son for safekeeping until he got out of prison. But a week after he was released on parole, he shot and killed a grocery store owner in downtown Mansfield — and was then shot and killed by Mansfield police officers who responded to the call.

Kulig still has the portrait as a reminder of a different life, he said. He recalled Robert saying he wanted to be a good father to his son — the kind of father he himself never had.

He still thinks about the ripple effect of the choices we all make.

“How would things change if instead of relying on programs that are rather mechanical, we shift the focus of kids getting raised in community?” Kulig said.

“What if every adult asked themselves, what am I doing to be helpful to my community in raising our children?”